Panel 1

On April 13th & 14th, 2018, Cornell’s Department of German Studies hosted its Graduate Student Conference Flanking Maneuvers: Laterales Denken. The subject of the first panel was the in-between of fiction and faction, friction and fraction, picture and depicted, stage and audience. Attempting to overcome these divisions, conference participants reflected on potential strategies that could help to bridge the praxis of differentiation and shape an understanding of the lateral. However, shifting these relations also enabled conference participants to question scenic devices, descriptions, and figurations of inclusion and exclusion. The panel explored the epistemic potential of what might be conceived as “lateral thinking” and showed what a lateral reading of culture might look like.

In the first presentation, Annekatrin Sommer (Cornell) elaborated her research on Kippfiguren in which she analyzed post-Oedipal narratives through the lens of multistable perception. After elaborating on the visual phenomenon of ambiguous images, Sommer discussed optical illusions that permit two distinct images to share the same composition. This doubling effect forces the brain to make a decision between the two images, evoking an oscillating effect of multistability. Sommer went on to discuss the epistemological potential of the Kippfigur as a heuristic for approaching literature. Central to Sommer’s presentation were the questions of how to identify literary texts that contain Kippfiguren and the benefits that can be gained by applying this approach to the study of literature and visual culture. It is conceivable that both manifestations of the image have an equal ontological claim within a given environment—an outcome that effectively subverts any temptation to think of the images in a hierarchical framework.

The second presenter, Hannah Fissenebert (HU Berlin/ UC Berkeley), re-examined the use of spatial metaphors to show how they qualify as “paradigmatic modes of thinking.” According to Fissenebert, time and space are essential for the narration and figuration of dramatic works. Space seems to hold a privileged position within drama theories insofar as the poetological dimensions are expressed through metaphors like ‘anatomy,’ ‘tectonic,’ or ‘architecture.’ Fissenebert observed that neither the temporal aspects of drama narratives, nor the temporality of theater itself have played a crucial role in developing a theoretical vocabulary for the theater. In an effort to reconsider the conceptual structures that permeate drama theory, Fissenebert proposed a different, lateral approach to these texts, which would privilege a genealogical mode of engaging their paradigmatic metaphors.

The final presenter of this panel, Arne Sander (HU Berlin/ Cornell), discussed notions of decontextualizing time and space with the help of new technologies. His talk aimed at a conscious engagement with the time, temporality, and contemporaneity of images. By emphasizing the spatiotemporal dimensions of art works and literature, which in some moments would merge indiscernibly, Sander showed how notions of “the real,” “the truthful,” or “the genuine” are being destabilized by new technologies. The current and the virtual are being superimposed; they appear merely as simulacra. Yet, according to Sander, a critical consideration “from the margins” might offer a perspective that historicizes these impositions and constructions within a constantly shifting episteme. (Marius Reisener)

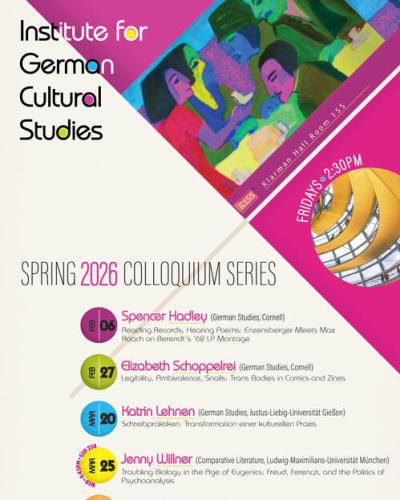

The first conference day ended with a grand finale. The keynote lecture “Nebenschauplätze: Looking Askew in Contemporary Art” presented by Prof. Svea Braeunert from the University of Cincinnati turned to contemporary visual works of art that oppose and problematize vertical and binary orders of knowledge and thereby indicate a paradigmatic shift, most prominently embodied through the use of drone warfare post- 9/11.

“As the ubiquitous vision and remote engagement of drones redefine contemporary policing and warfare, their impact is filtering into art and visual culture, generating new investigations into issues of visibility, technology and fear,” Braeunert argued, and revealed the unique potential of art to further our understanding of, and give visual form to, modern drone warfare and digital surveillance. She illuminated how art participates in a far-reaching discussion about the rapidly shifting conditions of perception – of seeing, and being seen – made possible by advanced technology.

Braeunert’s analysis concentrated on two artworks by Louise Lawler and Hito Steyerl and their specific use of visual techniques of distortion lauch as anamorphosis, or apophenia, to show the impact of drone warfare and how it embodies the condensations and displacements of the current technological disposition.

Louise Lawler’s No Drones pictures Mustang-Staffel (Mustang Squadron), a 1964 painting by the German artist Gerhard Richter that depicts a group of Mustang bombers, the planes that were used by Allied forces to help defeat the Nazis in World War II. Lawler photographed the painting at an oblique angle so that we see the hanging device attached to the stretcher bars behind the canvas. The title of the work is both a literalism (there were no drones during World War II) and a contemporary call to end the production and use of airborne instruments of war.

Anamorphosis is a distorted projection or perspective requiring the viewer to use special devices or occupy a specific vantage point to reconstitute a hidden or otherwise indecipherable image. The use of anamorphic images in Louise Lawler’s work questions the idea of linear perspective, unsettling the viewing subject and the idea of a central or even certain point of view. There is no fixed position, only fractured, multiplied and polyvalent positions. The viewing subject is forced to give up its visual mastery. Its own position begins to shift, which leads to uncertainty and discomfort.

The work by Hito Steyerl’s that Braeunert discussed, depicts an image from the Snowden files of an aerial attack in Gaza. It is labeled “secret”. Yet one cannot see anything on it. Rather, it turns blindness into an image.

Steyerl argues that “[n]ot seeing anything intelligible is the new normal. […] Seeing is superseded by calculating probabilities. Vision loses importance and is replaced by filtering, decrypting, and pattern recognition. Snowden’s image of noise could stand in for a more general human inability to perceive technical signals unless they are processed and translated accordingly” (Steyerl, A Sea of Data). The drone war is a secret and invisible war; its secrecy is based on invisibility—an invisibility that is tied to the exceptional conditions of such warfare. As a consequence, one of the pressing questions is how to visualize civilian victims of drone strikes.

The role of the witness of the conditions of warfare, which are conditions of urgency that put into question documentary trust and also the possibility of action and agency (specifically of active aesthetic agency) coincides with the decision to give visibility to that which is sublimated by war and death. An asymmetrical scopic regime thus becomes the visual manifestation of an asymmetrical war in which the power to see without being seen is supplemented with the power to harm without being harmed. In short, drone warfare creates a hierarchy, a vertical typology that changes the way enemies are being seen. Approaching from above, the attacker is neither face to face with them, nor on the same ground. Hovering above the enemies leads to a different attitude towards them. The tight connection between drone warfare, asymmetrical warfare, and the concomitant asymmetry of looking supports the definition of drone warfare as a specific scopic regime, which can best be brought into the open and reflected upon by exploring ways of making the unseen visible. Artists construe the drone both in terms of an object, a thing to be looked at, and as a subject, a viewing machine that facilitates looking.

Both Lawler and Steyerl question the alleged certainty of central perspective and vertical positions, thereby shifting our common understanding and opening up new meanings: what has hitherto remained unseen can thus come into view. Braeunert interpreted their art works as metapictures or images that show us how to see the world through the lens of lateral thinking and counteract the obfuscation of the brutal hierarchies characteristic of contemporary warfare. (Annekatrin Sommer)

Panel 2

On Saturday, April 14th, the 2018 German Graduate Student Conference Flanking Maneuvers: Laterales Denken kicked off its second day with a panel on “Flanking History.” After the opening panel and keynote lecture the previous afternoon, this panel turned its attention from questions of visuality to historical philosophical and political problems in 18th and 19th century literature, keeping in mind keynote speaker Svea Bräunert’s invitation to consider how literary analysis might profit from lateral engagements with visual studies. The panel featured two speakers: Matteo Calla (Cornell) and Luke Rylander (Indiana University, Bloomington). Calla’s talk, “Charismatic Media: Klopstock’s Gelehrtenrepublik / Trump’s Twitter,” opened with an analysis of charisma in the political thought of Max Weber and went on to investigate appropriations and transformations of Weberian charisma in two political and medial contexts: Klopstock in 18th century Germany and Trump in contemporary America. Calla was able to show how Trump and Klopstock have in common—surprisingly, but vitally—certain “innovative” and effective rhetorical strategies for appropriating the cutting-edge media technologies and forms of social-media participation of their day. Thus, both Klopstock and Trump generated a new socially-acknowledged power independent of traditional institutional authority. Klopstock, argued Calla, confronts in his Gelehrtenrepublik the absence of a contemporaneous audience who recognize charismatic (poetic) leadership, priming them effectively to do so by reconfiguring channels of media distribution in such a way that Klopstock becomes directly linked to his readers and they to one another. This was achieved mainly through a subscription service garnering 3,480 subscribers whose names Klopstock printed in the distributed text. Like Klopstock’s Gelehrtenrepublik, Twitter represents an audience’s reactions to itself in the form of likes and comments. Trump’s Twitter strategy exploits this potential of the medium to represent charisma by making controversial statements that elicit a barrage of positive and negative responses represented alongside all posts, demonstrating Trump’s effectiveness to his audience and confirming his authority. Calla concluded that the comparison with Klopstock ultimately suggests that Trump’s use of Twitter is not primarily about offering “alternative facts” to those found in traditional news media, but rather about utilizing the potential of social media to represent socially-acknowledged power or charismatic authority. This argument reveals authoritarian potential behind a medium typically praised for its democratizing structure.

Luke Rylander’s talk, “Vital Aesthetics: Schiller’s Appropriation of Vitalism in Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen,” traced the historical change between Plato and Schiller in the relationship between the political and moral value of art and Idealist epistemology, finding that while for the former they were incompatible, for the latter they were necessary bedfellows. The explanation for this difference, Rylander argued, lies in the fact that for Schiller the nascent discourse of vitalism accomplished a previously implausible reconciliation between Idealism and Art through new notions of biological development and Bildung. Rylander showed how, starting with Blumenbach around 1780, the vitalist movement in natural science revolutionized discourses on form, replacing older mechanistic models with concepts of form as autopoietic emergence and expressions of vital forces. This argument stressed the debt of Schiller’s moral philosophy not so much to Kant’s critical work, as per received scholarly accounts, but rather to new natural-scientific thinking that was to be called “biological” after 1800. In both Rylander’s and Calla’s talks, the topos of laterality was addressed through historical cross-linking as well as methodological intersecting. (Juan-Jacques Aupiais)